Carlos Courtney

Growth Partners

The Comparison Trap: How It Fools Top Performers into Overestimating Their Success

Ever feel like you're doing great, only to realize you've got a lot more to learn? It's a common feeling, especially for those who are really trying their best. We often get caught up in comparing ourselves to others, which can mess with how we see our own progress. This trap makes it tough to know if we're actually as good as we think we are, or if we're selling ourselves short. Let's break down why this happens and how to get a clearer picture of where we stand.

Key Takeaways

The Dunning-Kruger effect shows that people with low skill in an area often think they're much better than they are, while skilled people tend to think they're not as good.

This happens because the skills needed to be good at something are often the same skills needed to know if you're good at it.

In work, this can lead people to overestimate their contributions and resist helpful feedback, slowing down their growth.

True experts know there's always more to learn and are aware of the limits of their knowledge, showing intellectual humility.

Getting honest feedback, especially from a trusted Growth Partner, and practicing self-reflection are key to breaking free from the comparison trap and seeing yourself more clearly.

Understanding The Dunning-Kruger Effect

Ever met someone who's absolutely certain they're brilliant at something, even when it's pretty obvious they're not? That's often the Dunning-Kruger effect in action. It's a mental quirk where folks who don't know much about a subject tend to think they know a lot. It's like they're too inexperienced to even realize how little they actually know.

The Genesis of a Cognitive Bias

This whole idea really kicked off with a quirky bank robber named McArthur Wheeler back in 1995. He robbed two banks in broad daylight, no disguise, and was genuinely shocked when he got caught. His reasoning? He'd smeared lemon juice on his face, thinking it would make him invisible to cameras. This bizarre incident got psychologist David Dunning thinking: how can someone be so wrong and so confident about it? He teamed up with Justin Krueger, and together they did a study. They tested people on things like humor and logic, then asked them to guess how they did. The results were wild: the folks who did the worst thought they were way above average, while the actual high-achievers tended to downplay their success. It turns out, the skills needed to be good at something are often the same skills needed to know if you're good at it. If you don't have the skills, you can't spot your own mistakes.

The Double Burden of Incompetence

This leads to what's called a "double burden." It's not just that people lack the ability to do well; they also lack the ability to see that they're not doing well. They're essentially blind to their own shortcomings. This makes it tough to improve because you don't even know you need to. It's like trying to fix a leaky faucet when you don't know the first thing about plumbing – you might make it worse without realizing it.

Metacognitive Deficiencies at Play

At its heart, the Dunning-Kruger effect is about metacognition, which is basically thinking about your own thinking. When this goes wrong, people have trouble accurately judging their own knowledge and skills. They don't know what they don't know. This blind spot creates a false sense of confidence. It's not that people are intentionally trying to fool themselves; it's a genuine lack of self-awareness. This is why understanding the Dunning-Kruger effect is so important for anyone looking to grow and improve.

Here's a quick look at how it plays out:

Unknown Unknowns: People often don't realize the full scope of what they don't know when entering a new area.

Confirmation Bias: Once someone believes they're good at something, they tend to notice things that prove them right and ignore things that suggest otherwise.

Self-Assessment Issues: It's just plain hard for most people to accurately rate themselves without clear benchmarks.

The core issue is a failure in self-awareness. Without the right skills, you can't recognize your own lack of them, leading to an inflated sense of competence.

It's a common human tendency, and recognizing it is the first step to getting past it.

The Illusion of Superiority

Unknown Unknowns and Uncharted Territories

Ever felt like you've got a handle on something, only to realize later there was a whole lot more to it than you initially thought? That's kind of what happens when we first dip our toes into a new area. We don't know what we don't know. It's like trying to navigate a dense forest without a map or even knowing what a map looks like. You might think you're just taking a short stroll, but you're actually miles from where you need to be, and you haven't even considered the rivers you'll need to cross or the mountains you'll have to climb.

This lack of awareness about the full scope of a subject is a big part of why we can feel so confident when we're just starting out. The skills needed to actually do something well are often the same skills needed to recognize how well you're doing it. If you don't have those skills, you can't spot your own mistakes or see how much better someone else might be.

Confirmation Bias Reinforcing False Beliefs

Once we form an idea about our own abilities, our brains tend to look for proof that we're right. We pay more attention to the times we succeeded and brush off the times we failed, maybe blaming it on bad luck or someone else. If we get feedback that's a bit vague, we'll likely interpret it in a way that makes us look good. It's a mental shortcut that helps us feel secure in our self-image, even if that image isn't quite accurate.

We tend to seek out information that confirms what we already believe and ignore anything that challenges it. This makes it hard to change our minds, even when faced with evidence that suggests we might be wrong.

The Above Average Effect and Illusory Superiority

It's a funny thing, but most people think they're better than average at most things. Seriously. Studies have shown that a huge number of people rate themselves as being above average drivers, better than average friends, and even more skilled than average at their jobs. This isn't just a little bit better; it's often a significant overestimation.

This tendency to see ourselves through rose-tinted glasses is called illusory superiority. It's like a built-in defense mechanism that makes us feel good about ourselves. But when it comes to performance, especially in professional settings, this can lead to some serious miscalculations about our actual contributions and capabilities. It's a gap between how we see ourselves and how we actually perform, and it's wider than we usually realize.

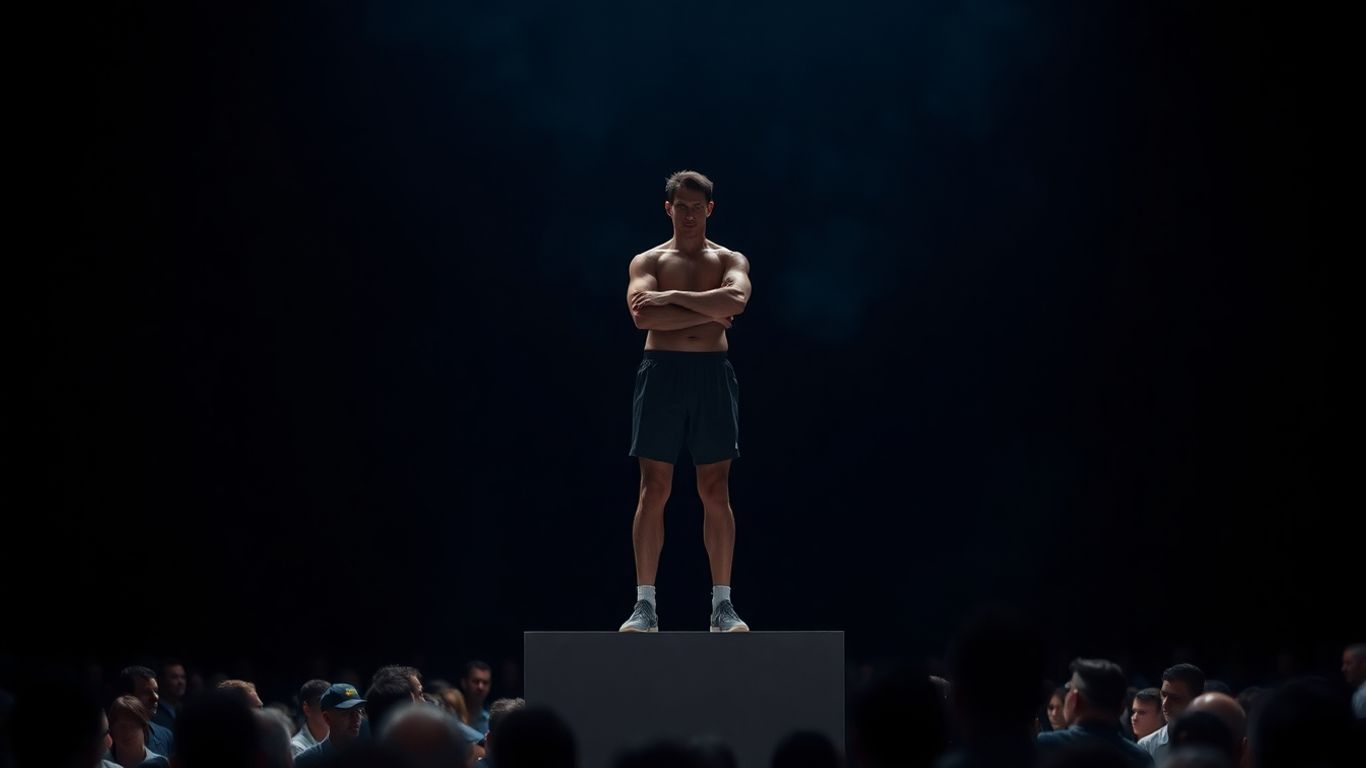

Navigating The Journey From Novice To Expert

So, you've just dipped your toes into something new, maybe a new skill at work or a hobby. It's exciting, right? You learn a few basics, and suddenly, you feel like you've got a pretty good handle on things. This initial burst of confidence is often called 'Mount Stupid.' It's that peak where you know just enough to think you know a lot, but you're blissfully unaware of how much you don't know. It's like learning a few chords on a guitar and thinking you're ready for a stadium tour.

The Peak of Mount Stupid

At this stage, your confidence is sky-high, often disproportionate to your actual skill. You might find yourself offering advice or making strong statements about the topic, even though your experience is minimal. This isn't necessarily arrogance; it's a natural byproduct of limited knowledge. You simply don't know what you don't know, and that ignorance can feel like knowledge.

The Valley of Despair

But don't get too comfortable on Mount Stupid. As you continue to learn, you start to see the sheer vastness of the subject. Suddenly, all those things you didn't know come crashing down on you. Your confidence plummets. This is the 'Valley of Despair.' It's where many people get discouraged and give up, feeling overwhelmed by the complexity and their own perceived lack of ability. It's a tough spot, realizing that what you thought was simple is actually incredibly intricate.

The Slope of Enlightenment and Plateau of Sustainability

If you push through the Valley of Despair, you start climbing the 'Slope of Enlightenment.' Here, your confidence begins to rise again, but this time, it's matched by growing competence. You're learning, practicing, and getting better. Your confidence is now more grounded in actual skill. Eventually, you reach the 'Plateau of Sustainability.' This is where you have a solid grasp of the subject, and your confidence is appropriately aligned with your abilities. You're not overconfident like on Mount Stupid, nor are you drowning in doubt. You know what you know, and you're aware of what you still need to learn. It's a place of steady progress and realistic self-assessment.

The journey from not knowing to knowing isn't a straight line. It's a rollercoaster of confidence and competence, with some steep drops and gradual climbs. Recognizing which stage you're in is the first step to moving forward effectively.

The Comparison Trap In Professional Settings

It's pretty common to see this whole Dunning-Kruger thing pop up at work. You know, where folks who aren't really all that skilled think they're doing a bang-up job. It's like they're in their own little bubble, totally unaware of how much they don't know.

Overestimating Performance and Contribution

This is where it gets tricky. People genuinely believe they're crushing it, contributing way more than they actually are. A study showed that a whopping 95% of managers thought they were in the top half of their peers. Statistically, that's just not possible, right? It leads to this inflated sense of self that can really mess with team dynamics and project outcomes.

Resistance to Feedback and Limited Growth

When you think you're already awesome, why would you listen to someone telling you otherwise? That's the trap. People stuck in this mindset often brush off feedback, seeing it as criticism rather than a chance to get better. It's a major roadblock to learning and growing professionally. They might even get defensive or dismissive when someone tries to offer constructive thoughts.

The Role of a Growth Partner in Calibration

So, how do you get out of this funk? Having someone, a "growth partner," can be a game-changer. This person isn't just a boss or a coworker; they're someone who can offer honest, objective feedback. They help you see things more clearly, calibrate your self-perception with reality, and point out blind spots you might have. Think of them as a reality check, but a supportive one.

Here's what a good growth partner might do:

Listen when you're struggling with something.

Share their own experiences with similar issues.

Help you brainstorm ways to tackle challenges.

Act as a sounding board for your ideas.

Review your work and point out what you might have missed.

Encourage you to keep going when things get tough.

Believing you're already at the top means you stop climbing. The real pros, the ones who truly know their stuff, are usually the ones who are most aware of how much more there is to learn. They're humble about their knowledge because they understand the vastness of what they don't know.

Expert Underestimation and Intellectual Humility

It might seem odd, but sometimes the people who know the most are the ones who are least sure of themselves. This isn't about lacking confidence; it's about a deep awareness of how much more there is to know. True experts understand the intricate details and the many shades of gray in their field. They know the edges of their knowledge and are comfortable admitting when they don't have all the answers.

The Nuance of Expertise

When you've spent years working in a specific area, you start to see all the little complexities that beginners miss. You realize that simple answers often don't cover the whole story. This deep dive into a subject means you're more aware of the vastness of what you don't know. It's like looking at a map; the more you explore, the more you see how much territory is still uncharted.

Awareness of Knowledge Boundaries

Experts tend to be pretty good at spotting the limits of their own understanding. They know which questions they can answer confidently and which ones require more thought or research. This self-awareness stops them from making bold claims they can't back up. It's a sign of maturity in learning, recognizing that absolute certainty is rare.

The Value of Not Knowing

There's a certain freedom in admitting you don't know something. It opens the door to learning and discovery. For experts, this isn't a weakness; it's a strength. It means they're open to new information and different perspectives.

True mastery isn't about having all the answers, but about being comfortable with the questions and the ongoing process of finding out.

Think about it this way:

Novices: Might think they've got it all figured out after learning a few basics.

Intermediate Learners: Start to see the complexity and their confidence dips.

Experts: Understand the nuances and are aware of the vast unknowns, leading to more measured confidence.

This careful approach is what keeps them growing and prevents them from falling into the trap of overconfidence that can hold others back.

Overcoming The Comparison Trap

So, you've realized you might be caught in this comparison trap, maybe even a bit of that Dunning-Kruger effect we talked about. It's a tough pill to swallow, admitting you might not be as hot stuff as you thought. But hey, recognizing it is half the battle, right? The real work starts now, and it's all about getting a clearer picture of where you actually stand.

Recognizing Your Own Vulnerability

First off, let's just accept that none of us are immune to this. It doesn't matter if you're a seasoned pro or just starting out; we all have blind spots. Thinking you're above it all is actually a pretty good sign you're right in the thick of it. It's like trying to see your own nose without a mirror – pretty much impossible.

Acknowledge the possibility: Just entertain the idea that your self-assessment might be a little off. No need to go into a full-blown crisis, just a quiet "what if?"

Embrace the beginner's mind: Even if you're good at something, try approaching it sometimes like you're learning it for the first time. What assumptions are you making? What might you be missing?

Watch out for "easy" wins: When things feel too easy, or you're crushing it without much effort, it's a good time to pause. Are you truly skilled, or did you just get lucky or land in a situation that played to your strengths?

It's easy to get comfortable in our own little bubble, especially when things are going well. We start to believe our own hype, and before we know it, we're comparing ourselves to people we think are on our level, but who might actually be way ahead, or worse, we're comparing ourselves to people who are struggling, making us feel better without actually improving.

The Power of External Feedback

This is where things get really interesting, and honestly, a bit uncomfortable. You need other people to tell you what's up. Not your buddies who will just nod along, but people who actually know their stuff and aren't afraid to be straight with you. Think of it like getting a second opinion from a doctor – you want someone who's going to be honest, even if the news isn't great.

Seek out honest critics: Find people who have a good grasp of the area you're interested in and who you trust to give you real feedback, not just praise. This could be a mentor, a senior colleague, or even a peer who's known for being direct.

Ask specific questions: Instead of a vague "How am I doing?", try asking things like, "What's one thing I could have done better in that presentation?" or "Where did you see the biggest gap in my approach to that project?"

Listen without defending: This is the hard part. When you get feedback, try to just absorb it. Don't immediately jump in with excuses or explanations. Just hear them out. You can process it later.

Cultivating Metacognitive Awareness

Metacognition is just a fancy word for thinking about your thinking. It's about being aware of your own thought processes, your biases, and how you arrive at your conclusions. It's like having an internal quality control system for your brain.

Regular self-reflection: Set aside time, maybe weekly, to just think about your work, your decisions, and your progress. Ask yourself: Why did I make that choice? What assumptions was I operating under? Was I too confident or not confident enough?

Journaling: Writing things down can really help clarify your thoughts. Documenting your projects, your challenges, and your learning can provide a tangible record to look back on and see patterns you might otherwise miss.

Mindfulness: Practicing mindfulness can help you become more aware of your thoughts and feelings in the moment, without getting swept away by them. This can make it easier to catch yourself when you're falling into a comparison trap or overestimating your abilities.

Moving Beyond the Trap

So, we've talked about how easy it is to fall into the comparison trap, especially when we're doing well. It's like our brains play tricks on us, making us think we're way ahead when we're really just treading water. The Dunning-Kruger effect shows us that the skills needed to be good at something are often the same skills needed to know if you're actually good. This means those who aren't great at a task often don't even realize it, while the real pros might be a bit too hard on themselves. The trick is to stay grounded. Keep learning, ask for honest feedback, and remember that true skill comes with a healthy dose of knowing what you don't know. It's a constant balancing act, but one worth doing if you want to actually grow instead of just feeling like you're winning.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Dunning-Kruger effect in simple terms?

Imagine you're learning something new, like playing a video game. At first, you might think you're pretty good because you know a few basic moves. That's the Dunning-Kruger effect kicking in! It's when people who don't know much about something think they know a lot more than they actually do. They're too new to realize how much they *don't* know.

Why do people who are bad at something think they're good?

It's a bit of a brain trick! The skills you need to be good at something are often the same skills you need to know if you're good or not. So, if you're not good at, say, telling jokes, you might not be able to tell if your jokes are actually funny. You lack the understanding to see your own mistakes.

Do really smart people ever think they're not good enough?

Yes, surprisingly! Experts, who are actually very skilled, often realize how much more there is to learn. They understand the topic so well that they know how complex it is. This makes them a bit more humble and sometimes they might even underestimate how much better they are than others.

How does comparing ourselves to others make this worse?

When we only look at others, especially if we don't really know how good they are, we can get a false sense of how we measure up. If we see people who are clearly struggling, we might think we're doing great, even if we're just slightly better. It's like comparing yourself to someone who just started learning to swim when you're already a decent swimmer – you might feel like a champion, but there's still a lot to learn.

Can the Dunning-Kruger effect cause problems at work or school?

Absolutely. If someone thinks they're doing a fantastic job when they're actually not, they might not listen to advice or try to improve. This can lead to mistakes, missed opportunities, and frustration for everyone around them. It’s hard to grow if you don’t think you need to.

What's the best way to avoid falling into the Dunning-Kruger trap?

The best defense is to be open to learning and to ask for honest feedback from people you trust, especially those who know more than you. Also, try to think about what you *don't* know. Regularly asking yourself 'What else could I learn here?' or 'What am I missing?' can help keep your confidence in check and in line with your actual skills.